The Mechanics and Meaning of That Ol' Dial-Up Modem Sound

Pshhhkkkkkkrrrrkakingkakingkakingtshchchchchchchchcch*ding*ding*ding"

Of all the noises that my children will not understand, the one that is nearest to my heart is not from a song or a television show or a jingle. It's the sound of a modem connecting with another modem across the repurposed telephone infrastructure. It was the noise of being part of the beginning of the Internet.

I heard that sound again this week on Brendan Chillcut's simple and wondrous site: The Museum of Endangered Sounds. It takes technological objects and lets you relive the noises they made: Tetris, the Windows 95 startup chime, that Nokia ringtone, television static. The site archives not just the intentional sounds -- ringtones, etc -- but the incidental ones, like the mechanical noise a VHS tape made when it entered the VCR or the way a portable CD player sounded when it skipped. If you grew up at a certain time, these sounds are like technoaural nostalgia whippets. One minute, you're browsing the Internet in 2012, the next you're on a bus headed up I-5 to an 8th grade football game against Castle Rock in 1995.

The noises our technologies make, as much as any music, are the soundtrack to an era. Soundscapes are not static; completely new sets of frequencies arrive, old things go. Locomotives rumbled their way through the landscapes of 19th century New England, interrupting Nathaniel Hawthorne-types' reveries in Sleepy Hollows. A city used to be synonymous with the sound of horse hooves and the clatter of carriages on the stone streets. Imagine the people who first heard the clicks of a bike wheel or the vroom of a car engine. It's no accident that early films featuring industrial work often include shots of steam whistles, even though in many (say, Metropolis) we can't hear that whistle.

When I think of 2012, I will think of the overworked fan of my laptop and the ding of getting a text message on my iPhone. I will think of the beep of the FastTrak in my car as it debits my credit card so I can pass through a toll onto the Golden Gate Bridge. I will think of Siri's uncanny valley voice.

But to me, all of those sounds -- as symbols of the era in which I've come up -- remain secondary to the hissing and crackling of the modem handshake. I first heard that sound as a nine-year-old. To this day, I can't remember how I figured out how to dial the modem of our old Zenith. Even more mysterious is how I found the BBS number to call or even knew what a BBS was. But I did. BBS were dial-in communities, kind of like a local AOL. You could post messages and play games, even chat with people on the bigger BBSs. It was personal: sometimes, you'd be the only person connected to that community. Other times, there'd be one other person, who was almost definitely within your local prefix.

When we moved to Ridgefield, which sits outside Portland, Oregon, I had a summer with no friends and no school: The telephone wire became a lifeline. I discovered Country Computing, a BBS I've eulogized before, located in a town a few miles from mine. The rural Washington BBS world was weird and fun, filled with old ham-radio operators and computer nerds. After my parents' closed up shop for the work day, their "fax line" became my modem line, and I called across the I-5 to play games and then, slowly, to participate in the nascent community.

In the beginning of those sessions, there was the sound, and the sound was data.

Fascinatingly, there's no good guide to the what the beeps and hisses represent that I could find on the Internet. For one, few people care about the technical details of 1997's hottest 56k modems. And for another, whatever good information exists out there predates the popular explosion of the web and the all-knowing Google.

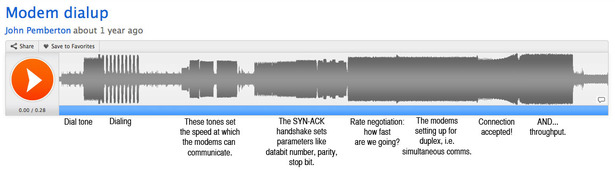

So, I asked on Twitter and was rewarded with an accessible and elegant explanation from another user whose nom-de-plume is Miso Susanowa. (Susanowa used to run a BBS.) I transformed it into the annotated graphic below, which explains the modem sound part-by-part. (You can click it to make it bigger.)

The frequencies of the modem's sounds represent parameters for further communication. In the early going, for example, the modem that's been dialed up will play a note that says, "I can go this fast." As a wonderful old 1997 website explained, "Depending on the speed the modem is trying to talk at, this tone will have a different pitch."

That is to say, the sounds weren't a sign that data was being transferred: they were the data being transferred. This noise was the analog world being bridged by the digital. If you are old enough to remember it, you still knew a world that was analog-first.

Long before I actually had this answer in hand, I could sense that the patterns of the beats and noise meant something. The sound would move me, my head nodding to the beeps that followed the initial connection. You could feel two things trying to come into sync: Were they computers or me and my version of the world?

As I learned again today, as I learn every day, the answer is both.