The coming 32-bit Apocalypse

After the main blockbuster WWDC keynote, Apple does a big “Platforms State of the Union” presentation aimed more specifically at the gathered audience of developers. It’s nicely situated between the nitty-grittiness of the specific WWDC sessions and the bird’s-eye overview you get in the general keynote, and it’s always full of interesting tidbits.

Buried in that presentation this year was news about the next phase of the macOS transition from 32-bit to 64-bit, a process that has been much longer and messier for the Mac than it was for iOS. Here’s a really brief timeline:

- June 2003: The PowerPC G5 CPU is the first 64-bit-capable chip to show up in a Mac, and with Mac OS X 10.3 Panther can theoretically address up to 8GB of RAM.

- April 2005: Mac OS X 10.4 Tiger allows for 64-bit processes under-the-hood—they can be spun off from another process or run via the Terminal.

- June 2005: Apple announces that it will begin using Intel processors, which are still primarily 32-bit. Whoops!

- August 2006: Apple launches the Intel Mac Pro with a 64-bit Woodcrest CPU; mainstream 64-bit Core 2 Duo Macs follow shortly afterward.

- October 2007: Mac OS X 10.5 Leopard launches with actual support for regular 64-bit apps; Universal Binaries can run on 32-bit and 64-bit Intel and PowerPC machines, covering four architectures within a single app. Unlike Windows, Apple never ships separate 32- and 64-bit versions of Mac OS X.

- August 2009: Mac OS X 10.6 Snow Leopard still runs on 32-bit chips, but for the first time everything from the apps to the OS kernel supports 64-bit operation. Snow Leopard’s 64-bit capabilities are a major component of Apple’s marketing push, which infamously includes “no new features.” However, most systems still default to loading the 32-bit kernel.

- July 2011: Mac OS X 10.7 Lion drops support for 32-bit Intel CPUs (Snow Leopard had already ended all support for PowerPC systems). Older Macs continue to default to the 32-bit kernel and 32-bit drivers, but new Macs launched in this era typically default to the 64-bit kernel.

- July 2012: OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion boots into the 64-bit kernel by default on all systems that support it, including a few that previously defaulted to the 32-bit kernel. In the process, a few 64-bit systems with 32-bit graphics drivers and 32-bit EFIs are dropped from the support list. That said, OS X can still run 32-bit apps.

That brings us to today. Even in High Sierra, as of this writing, all of Apple’s code is 64-bit—but you can continue to develop and run 32-bit apps as long as there’s not some other compatibility problem.

But this is the beginning of the end. High Sierra will, in Apple's own words, be the last macOS release that can support 32-bit macOS apps “without compromise.” And for apps distributed through the Mac App Store, there are two new dates to add to the timeline:

- January 2018: All new apps submitted to the Mac App Store need to be 64-bit only.

- June 2018: All new apps and updates to existing apps submitted to the Mac App Store need to be 64-bit only.

Apple hasn’t clarified what “without compromise” means, and presumably 32-bit apps from outside the Mac App Store will continue to run for at least the next year or two (if only via some kind of Rosetta-esque downloadable compatibility layer). But sooner rather than later, Apple is going to strip all the 32-bit libraries, apps, and codes out of macOS, just like it already did in iOS 11 this year.

This sounds disruptive, but, if anything, Apple has been remarkably conservative in its approach to 32-bit app support. It has been six years since a new macOS release ran on a 32-bit Mac; iOS went from entirely 32-bit to entirely 64-bit in just four years.

Because developers have had so much time, most mainstream apps are already 64-bit. Of the apps I regularly use, only the Dropbox client, Adobe’s apps, and the Audacity audio editing app are still 32-bit—the first two are pretty big, admittedly, though at least those companies have the resources to go 64-bit if Apple makes them put in the work. I’m sure there are lots of niche apps, particularly in businesses and schools, that are still 32-bit, either because they’re not maintained or because upgrading to a newer 64-bit version would cost money that these places don’t have. But for the majority of people, even if Apple shut 32-bit support off tomorrow, it wouldn’t be a major problem.

Finder and UI: High Sierra is really a lot like Sierra

I wrote last year that, after years of constantly tweaking the appearance of buttons and scroll bars and other UI elements throughout macOS’ long life, things seem to have settled down post-Yosemite. That remains true in High Sierra, which changes essentially nothing about the way the operating system looks or works. Window management, Mission Control, the Today View and Notification Center column, iCloud integration—it’s all right where Sierra left it. Last year’s review is the best place to read about iCloud Desktop and Documents and the disk space management tools, which are almost the same in High Sierra.

I say "almost" because Apple has added the ability to share files with other iCloud Drive users for collaborative editing from within apps or within the Finder. Open the iCloud Drive folder (or anything in your Desktop or Documents folders, if you're syncing that data with iCloud), right-click a file, head to the Share menu, and click Add People; if your app uses Apple's default Share menu, you can also share files from there as long as the file you have open is saved to iCloud Drive somewhere.

-

Sharing a file through iCloud.Andrew Cunningham

-

The UI looks the same as the one already in the Notes app.Andrew Cunningham

-

Sending a link via Messages.Andrew Cunningham

-

Once it's shared, you control access to your file from here.Andrew Cunningham

From there, sharing files works the same way it did in the Notes app in Sierra. Choose another High Sierra or iOS 11 user to share the file with, choose how to send them the link, and choose the level of access you'd like to give them, and you're done. The title bar will indicate when a file is shared, and the Add People entry in the Share menu becomes a Show People entry you can click to add more users, change access levels, remove users, or stop sharing entirely. Contacts you've shared with recently also show up in the Share menu so you can quickly share other files with them (the method you used to share the file is saved, too).

Another minor tweak arrives in the form of a new variant of the San Francisco typeface called San Francisco Pro that doesn’t replace the default system typeface but is available for use in apps and becomes the new default typeface in Notes. It’s similar to San Francisco, but you can spot minor differences if you look at them side by side (the lowercase a’s are a dead giveaway). The monospaced version of San Francisco (“SF Mono”) that iOS 11 uses in a couple of places is only visible in macOS in the Terminal, where it can replace the default Andale Mono if you want it to, but this was also available in Sierra.

Some of the additions that are in High Sierra will only be visible if you use certain apps in certain ways or if you own certain Mac hardware. For example, in Sierra, Apple added tabs to a bunch of first-party apps, including Maps, TextEdit, Terminal, Pages, Keynote, and others; Apple also opened the feature up to third parties as an API so they could put tabs in their own apps. High Sierra adds a new “show all tabs” screen that displays thumbnail versions of all the tabs you have open, à la Safari. Developers already using the tabs should get this new view for free with no update required.

The main issue, apart from the fact that I haven’t actually seen the tabs picked up in any of the third-party apps I use daily, is that implementation is inconsistent from app to app even within Apple’s own apps. Sometimes the Command-T keyboard shortcut works; sometimes it doesn’t. The Finder doesn’t get a Show All Tabs mode, for whatever reason. And High Sierra doesn’t fix any of this stuff.

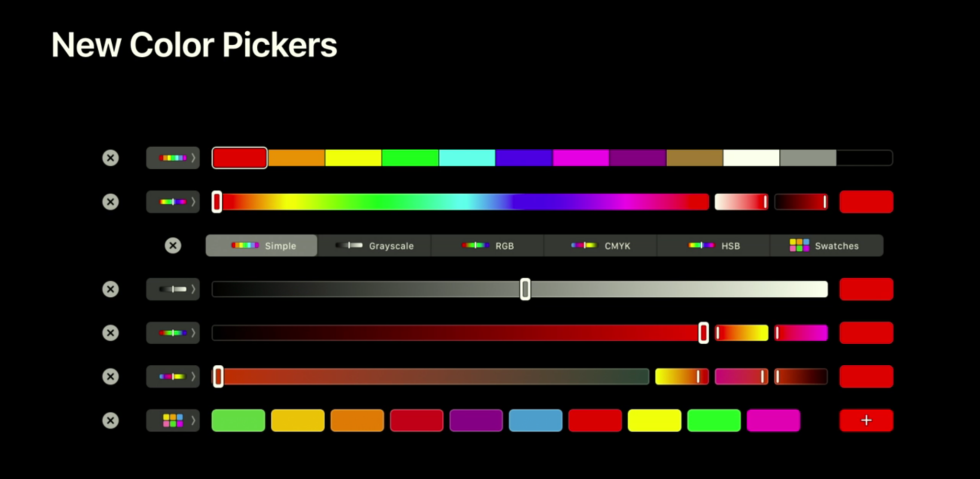

Touch Bar MacBook Pro owners may also notice a few new controls Apple has added to the default set of capabilities developers can control. When viewing a color picker, developers could previously choose to display either a few basic colors or a bar with a wide spectrum of colors. In High Sierra, developers also get grayscale, RGB, and CMYK color pickers, along with a “swatches” view that can display the user’s saved colors in apps like Keynote.

All things considered, though, High Sierra leaves the macOS user interface and the Finder right where Sierra left them, and Sierra in turn didn’t do much to build upon the UI tweaks and window management features El Capitan introduced two years ago. You’ll feel right at home, at least.

reader comments

218