Last year brought a surge of sketchy online ads to the Internet that tried to trick viewers into installing malicious software. Even credit reporting service Equifax was caught redirecting its website visitors to a fake Flash installer just a few weeks after reports of a data breach affecting as many as 145.5 million US consumers.

Now, researchers have uncovered one of the forces driving that spike—a consortium of 28 fake ad agencies. The consortium displayed an estimated 1 billion ad impressions last year that pushed malicious antivirus software, tech support scams, and other fraudulent schemes. By carefully developing relationships with legitimate ad platforms, the ads reached 62 percent of the Internet's ad-monetized websites on a weekly basis, researchers from security firm Confiant reported in a report published Tuesday. (Confiant has dubbed the consortium "Zirconium.") The ads were delivered on so-called "forced redirects," in which a site displaying editorial content or an ad suddenly opened a new page on a different domain.

Confiant CTO Jerome Dangu wrote the following in an email:

These forced redirects are a technical mechanism that can be leveraged to deliver a variety of malicious attacks, from those targeting businesses (affiliation fraud), to those targeting individual users (phishing scams, malicious downloads, fake updates etc.)... At a minimum, these forced redirects often make a website unusable for an everyday user, [and] at worse [visitors] are being directly attacked. People need to understand where the issues are coming from (often the website owner gets blamed, even as they themselves are a victim, too) and what the new risks are for them in an ad supported Internet.

Confiant said that most of the fake ad agencies have their own websites, Twitter accounts, and executive profiles on LinkedIn. One such agency called out in the report is known as Grandonmedia, whose website urges visitors to "Buy Website Traffic visitors to our loyal customers!" The Facebook profile for its CEO displays what appears to be a stock business photo, as did an earlier version of the CEO's LinkedIn profile

The agencies also rely on machine-generated content posted from its accounts on Facebook and Twitter. Grandonmedia bots issued content including "Lasting relations with reliable partner is the key to success in online marketing" and "Do you want to involve on your online profits? Don't hesitate to get in touch." Grandomedia officials didn't respond to messages seeking comment for this post.

Underscoring how much work organizers put into the Zirconium, each ad agency operates with a completely different set of IT tools, including TLS servers, domain registration, and ad-serving code. The purpose of the ad agencies is to develop trusted relationships with legitimate ad platforms. The ample supply of agencies allows one agency to step in and resume operations of a fellow agency once the forced redirects it pushes come to light. So far, only 20 of the 28 have actually been used. Tuesday's report lists the names and URLs of all 28 of the allegedly fake agencies. Confiant declined to name the 16 ad platforms that unwittingly forged relationships with the agencies.

"Zirconium's concept is to build independent marketing brands from scratch, en-masse," Tuesday's blog post said. "The vast majority [of fake agencies] went live in March/April 2017 according to Twitter account creation dates. At the date of this writing, eight remain unused, ready to be leveraged when the ones currently exploited dry out."

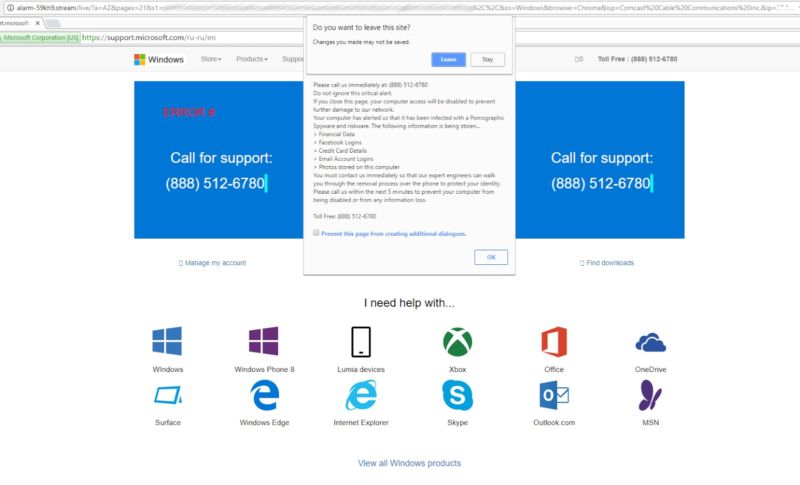

To evade detection, the servers hosting the ads perform forced redirects very selectively. Before redirecting a user, the servers attempt to fingerprint the individual's browser by taking stock of the user agent, the visiting IP address, the number of CPUs, and whether the computer is able to use WebGL. The fingerprint helps servers identify machines that may be used by security researchers so they don't experience the redirects. Zirconium relies on servers at beginads[.]com as its central gateway to manage ad demand. The fraudulent ads can be surprisingly effective. The one posted above uses a technique first described by Malwarebytes to display the authenticated URL of Microsoft in a tech-support scam.

Use of forced redirects has increased for three reasons: 1) Browser makers have grown more resistant to drive-by exploits, 2) the use of the often-exploited Adobe Flash for ads has declined, and 3) security companies have gotten better at detecting exploit code in online ads.While not as effective as malvertising exploits that install ransomware and other types of malware with no social engineering required, forced redirects remain an appealing alternative that's also cost-effective. Until publishers and ad platforms better organize to stamp out groups like Zirconium, the redirects are likely to remain a common Internet menace.

reader comments

141