This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

Unit 42 researchers identified a new cryptojacking worm we’ve named Graboid that's spread to more than 2,000 unsecured Docker hosts. We derived the name by paying homage to the 1990’s movie “Tremors,” since this worm behaves similarly to the sandworms in the movie, in that it moves in short bursts of speed, but overall is relatively inept.

There have been incidents of cryptojacking malware spreading as a worm, but this is the first time we see a cryptojacking worm spread using containers in the Docker Engine (Community Edition). Because most traditional endpoint protection software does not inspect data and activities inside containers, this type of malicious activity can be difficult to detect. The malicious actor gained an initial foothold through unsecured Docker daemons, where a Docker image was first installed to run on the compromised host. The malware, which was downloaded from command and control (C2) servers, is deployed to mine for Monero and periodically queries for new vulnerable hosts from the C2 and picks the next target at random to spread the worm to. Our analysis shows that on average, each miner is active 63% of the time and each mining period lasts for 250 seconds. The Docker team worked quickly in tandem with Unit 42 to remove the malicious images once our team alerted them of this operation.

Containerized Cryptojacking Worm

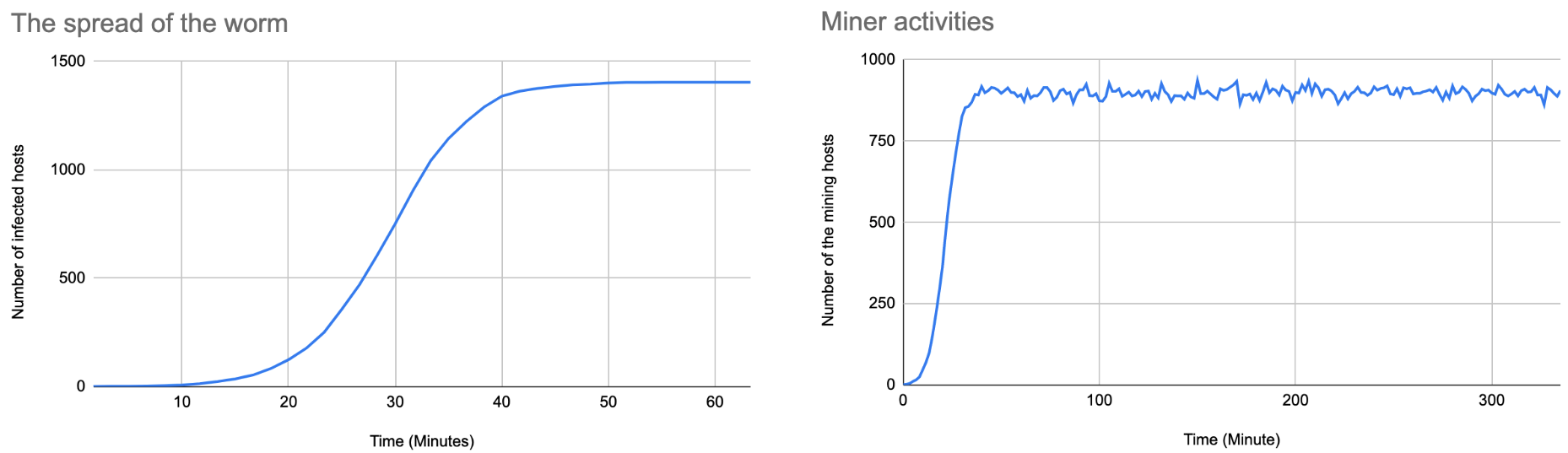

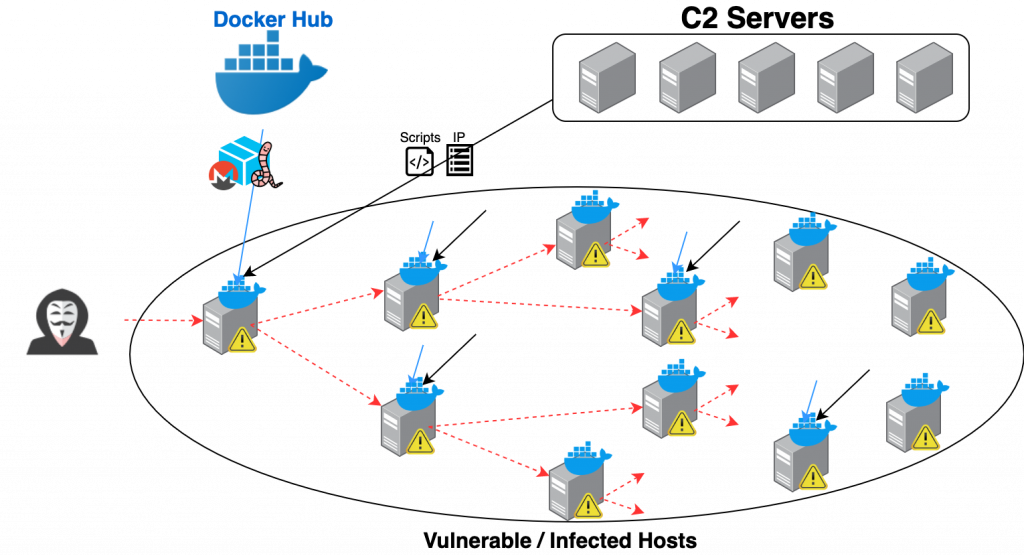

Figure 1. Cryptojacking worm activity overview

A quick Shodan search shows that show that more than 2,000 Docker engines are insecurely exposed to the internet. Without any authentication or authorization, a malicious actor can take full control of the Docker Engine (CE) and the host. The attacker leverages this entry point to deploy and spread the worm. Figure 1 illustrates how the malware is delivered and spread. The attacker compromised an unsecured docker daemon, ran the malicious docker container pulled from Docker Hub, downloaded a few scripts and a list of vulnerable hosts from C2 and repeatedly picked the next target to spread the worm. The malware, which we’ve named ‘Graboid’, carries out both worm-spreading and cryptojacking inside containers. It randomly picks three targets at each iteration. It installs the worm on the first target, stops the miner on the second target, and starts the miner on the third target. This procedure leads to a very random mining behavior. If my host is compromised, the malicious container does not start immediately. Instead, I have to wait until another compromised host picks me and starts my mining process. Other compromised hosts can also randomly stop my mining process. Essentially, the miner on every infected host is randomly controlled by all other infected hosts. The motivation for this randomized design is unclear. It can be a bad design, an evasion technique (not very effective), a self-sustaining system or some other purposes.

Below is a more detailed step-by-step operation:

- The attacker picks an unsecured docker host as the target and sends remote commands to download and deploy the malicious Docker image pocosow/centos:7.6.1810. The image contains a docker client tool that is used to communicate with other Docker hosts.

- The entry point script /var/sbin/bash in the pocosow/centos container downloads 4 shell scripts from the C2 and executes them one by one. The downloaded scripts are live.sh, worm.sh, cleanxmr.sh, xmr.sh.

- live.sh sends the number of available CPUs on the compromised host to the C2.

- worm.sh downloads a file “IP” that contains a list of 2000+ IPs. These IPs are the hosts with unsecured docker API endpoints. worm.sh randomly picks one of the IPs as its target and uses the docker client tool to pull and deploy the pocosow/centos container remotely.

- cleanxmr.sh randomly picks one of the vulnerable hosts from the IP file and stops the cryptojacking containers on the target. cleanxmr.sh stops not only the cryptojacking container the worm deploys (gakeaws/nginx) but also few other xmrig-based containers if they are running.

- xmr.sh randomly picks one of the vulnerable hosts from the IP file and deploys the image gakeaws/nginx on the target host. gakeaws/nginx contains an xmrig binary that is masqueraded as nginx.

Step 1 to Step 6 is repeated periodically on every compromised host. The last known refresh interval is set to 100 seconds. The refresh interval, the shell scripts, and the IP file are all downloaded from the C2 after the pocosow/centos container is launched.

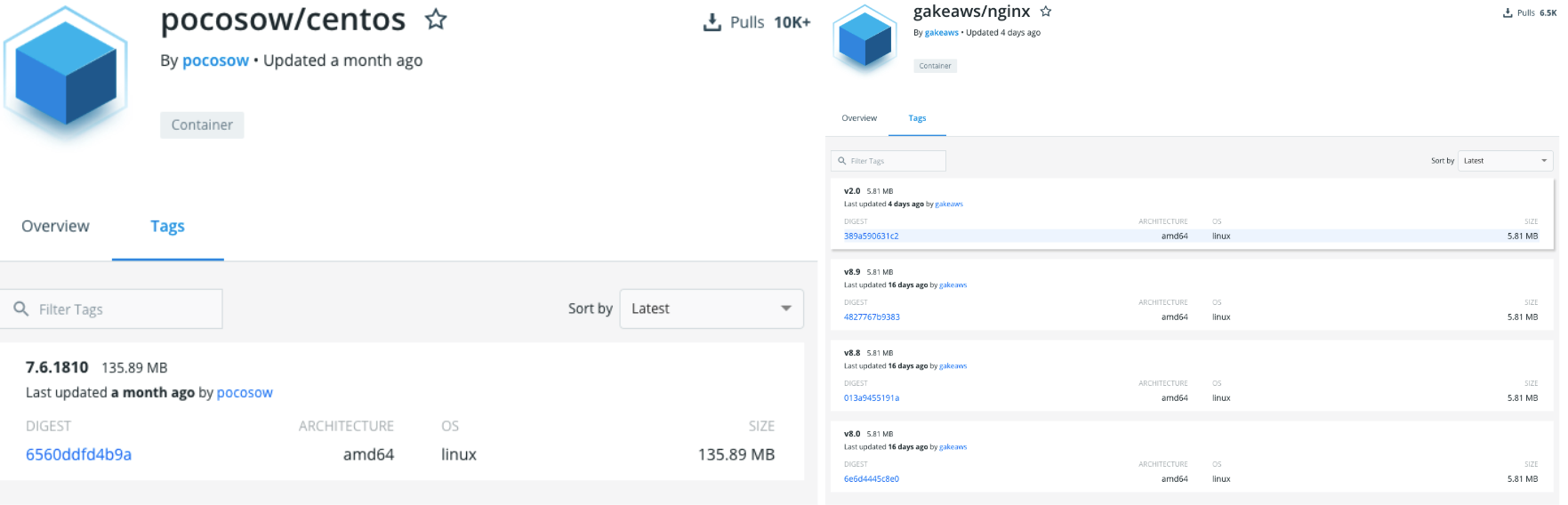

At the time of writing, Docker image pocosow/centos has been downloaded more than 10,000 times and gakeaws/nginx has been downloaded more than 6,500 times, as shown in Figure 2. We also noticed that the same user (gakeaws) published another cryptojacking image, gakeaws/mysql, that has the identical content to gakeaws/nginx.

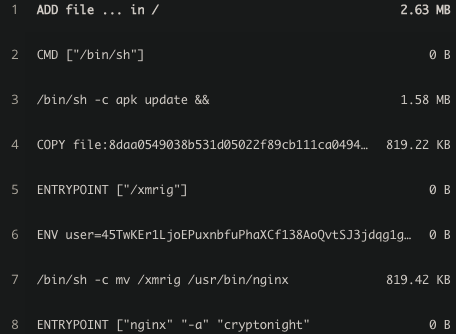

The malicious intent of the pocosow/centos image can’t be known until the shell scripts are downloaded and executed inside the container. However, the malicious intent of the gakeaws/nginx image can be easily spotted from its image build history. As shown in Figure 3, it simply renames the xmrig binary to nginx at the build time (Line 7). Even the payment address is hard-coded to an environment variable during the build time (Line 6).

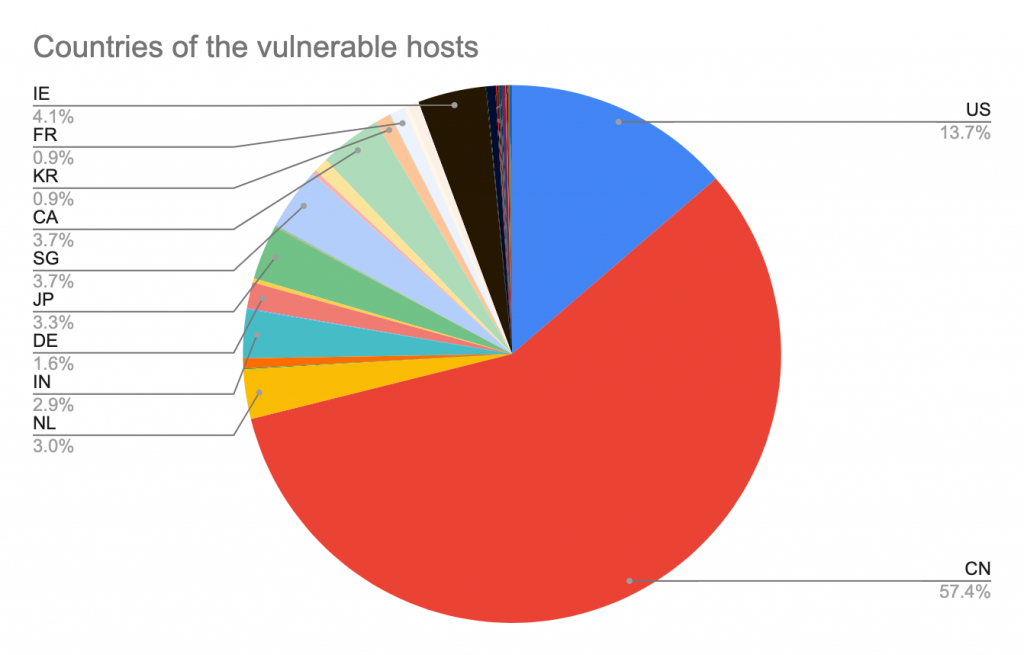

Figure 4 shows the location of the 2,034 vulnerable hosts listed in the IP file -- 57.4% of the IPs originated from China, followed by 13% from the U.S. We also noticed that out of the 15 C2 servers that the malware uses, 14 hosts are listed in the IP file and the other one host has more than 50 known vulnerabilities. It indicates that the attacker likely compromised these hosts and used them as C2 servers. With the control of the Docker daemon, it is straightforward to deploy a web server container (e.g., httpd, nginx) and place the payload there.

Figure 2. Malicious Docker images on Docker Hub

Figure 2. Malicious Docker images on Docker Hub

Figure 3. The image history of gakeaws/nginx

Figure 3. The image history of gakeaws/nginx

Figure 4. Countries of the vulnerable hosts in the IP file

Figure 4. Countries of the vulnerable hosts in the IP file

Worm Simulation

To better understand the effectiveness of the worm and its overall mining power, we created a simple Python program to simulate the worm. Assume that there are 2,000 hosts in the IP file, 30% of these hosts fail during the operation, a 100-seconds refresh interval and one CPU on each compromised host. The experiment simulates a 30-day campaign. We are interested in finding out:

- How long does it take for the worm to spread to all the vulnerable Docker hosts?

- How much mining power does this malicious actor own?

- How much time does each miner stay active on an infected host?

The left part of Figure 5 shows how fast the worm spreads. It takes about 60 minutes for the worm to reach all the 1,400 vulnerable hosts (70% of the 2,000+ hosts). The right part of Figure 5 shows the overall mining power of the compromised hosts. There are, on average, 900 active miners at any time. In other words, the malicious actor owns a 1,400 node mining cluster that has at least 900 CPU mining power. Because miners on the infected hosts can randomly start and stop, each miner is only active 65% of the time and each mining period lasts for only 250 seconds on average.

Conclusion

While this cryptojacking worm doesn’t involve sophisticated tactics, techniques, or procedures, the worm can periodically pull new scripts from the C2s, so it can easily repurpose itself to ransomware or any malware to fully compromise the hosts down the line and shouldn’t be ignored. If a more potent worm is ever created to take a similar infiltration approach, it could cause much greater damage, so it’s imperative for organizations to safeguard their Docker hosts.

Below is a list of best practices for organizations to help prevent from being compromised:

- Never expose a docker daemon to the internet without a proper authentication mechanism. Note that by default the Docker Engine (CE) is NOT exposed to the internet.

- Use Unix socket to communicate with Docker daemon locally or use SSH to connect to a remote docker daemon.

- Use firewall rules to allowlist the incoming traffic to a small set of sources.

- Never pull Docker images from unknown registries or unknown user namespaces.

- Frequently check for any unknown containers or images in the system.

- Cloud security solutions such as Prisma Cloud or Twistlock can identify malicious containers and prevent cryptojacking activities.

Palo Alto Networks has shared our findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, in this report with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. For more information on the Cyber Threat Alliance, visit www.cyberthreatalliance.org.

Indicator of Compromise

Docker Images:

pocosow/centos:7.6.1810:

Digest: sha256:6560ddfd4b9af2c87b48ad98d93c56fbf1d7c507763e99b3d25a4d998c3f77cf

gakeaws/nginx:8.9:

Digest: sha256:4827767b9383215053abe6688e82981b5fbeba5d9d40070876eb7948fb73dedb

gakeaws/mysql:

Digest: sha256:15319b6ca1840ec2aa69ea4f41d89cdf086029e3bcab15deaaf7a85854774881

Monero Address: 45TwKEr1LjoEPuxnbfuPhaXCf138AoQvtSJ3jdqg1gPxNjkSNbQpzZrGDaFHGLrVT7AzM7tU9QY8NVdr4H1C3r2d3XN9Cty

C2 servers:

120.27.32[.]15

103.248.164[.]38

101.161.223[.]254

61.18.240[.]160

182.16.102[.]97

47.111.96[.]197

106.53.85[.]204

116.62.48[.]5

114.67.68[.]52

118.24.222[.]18

106.13.127[.]6

129.211.98[.]236

101.37.245[.]200

106.75.96[.]126

47.107.191[.]137

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.