The 9 Lives of the Spanish Prisoner, the Treasure-Dangling Scam That Won’t Die

It’s been around for centuries.

“A man in this country receives a letter from a foreign city,” reads a New York Times trend story from 1898, about a “common” scam being carried out by mail. Titled “AN OLD SWINDLE REVIVED”, the story details how the “Spanish Prisoner” scam generally begins:

“The writer is always in jail because of some political offense. He always has some large sum of money hid, and is invariably anxious that it should be recovered and used to take care of his young and helpless daughter by some honest man. He knows of the prudence and good character of the recipient of the letter through a mutual friend, whom he does not mention for reasons of caution, and appeals to him in time of extremity for help.”

Postal shakedowns were a simple, and sometimes effective, way of illicitly separating rich people from their money in the 19th century. What was in it for the good Samaritan, just opening his mail on a boring day? Well, the sender of the letter “is willing to give one-third of the concealed fortune to the man who will recover it,” according to the Times.

What happens next is the ask: before the treasure can be recovered, the writer just needs some money sent to him first. (The treasure, of course, never materializes.)

Sound familiar? The so-called “Spanish Prisoner” scam is still around: just this week, a top Nigerian fraud artist was arrested for his part in carrying out similar swindles via email. And the 1898 Times description of the scam’s broad outlines remains remarkably accurate, save for a few technological details.

The swindle came to be known as the “Spanish Prisoner” because, often, the letter-writer claimed to be holed up in a Spanish jail, for reasons arising from the Spanish-American War. “The letter is written on thin, blue, cross-lined paper, such as is used for foreign letters, and is written as fairly well-educated foreigners write English, with a word misspelled here and there, and an occasional foreign idiom,” the 118-year-old Times story notes.

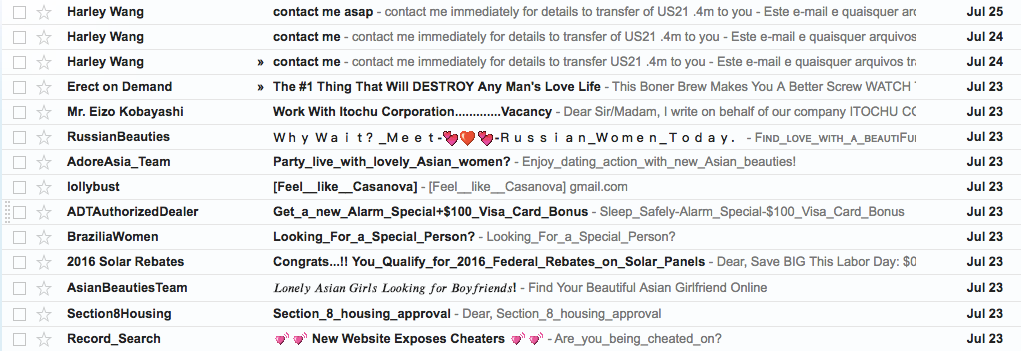

Modern readers, though, are likely more familiar with its more modern variant: official-looking emails from Nigeria, which ask the recipient to send money—often thousands of dollars—to unlock a massive treasure, which has been tied up by government officials or otherwise encumbered in some abstruse way.

As in 1898, these entreaties at first blush might seem real but upon closer inspection hardly hold up. The English is a little broken, and the “official” seal of some Nigerian government agency doesn’t seem quite right. There’s an air of too much desperation.

And, yet, still, people fall for it, since the conceit of the scam isn’t that it will work every time, or even one out of a hundred times. You only need a few suckers, in other words, to make millions. One victim in the U.S. lost $5.6 million to scammers. The recently arrested Nigerian spam-kingpin was said to have hauled in around $60 million in ill-gotten gains.

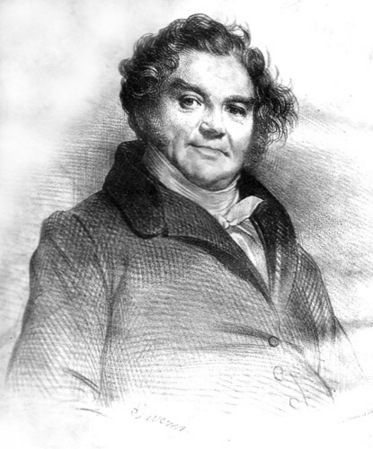

Eugène François Vidocq, the father of modern criminology. (Photo: Public domain)

But even in the days when you had to hand-write letters the scam was astonishingly successful. Eugène François Vidocq, who is called the father of criminology, documented in his memoirs a version of it perpetrated by prisoners in early 19th century France. This was well before the Spanish-American War, when the scheme was then known as “letters from Jerusalem.”

Vidocq, who, before he founded France’s civilian police corps was a criminal himself, saw firsthand the letters while he was imprisoned in a jail in Bicètre, in rural France.

“Sir,—You will doubtlessly be astonished at receiving a letter from a person unknown to you,” one such letter began, according to Vidocq’s recollection. The structure of this letter is savvy: before unleashing his tale of woe, the writer offers the carrot first: a casket containing 16,000 francs in gold as well as diamonds, which the writer says he and his master were forced to leave behind after they were detained while traveling. Having laid out the stakes, he continues, writing of his eventual supposed imprisonment, before, finally, the ask, which in this case is very subtle: “I beg to know if I cannot, through your aid, obtain the casket in question and get a portion of the money which it contains. I could then supply my immediate necessities and pay my counsel, who dictates this and assures me that by some presents, I could extricate myself from this affair.”

Vidocq wrote that 20 percent of such letters received some kind of reply, and, in some cases, prisoners made hundreds of francs from the letters, which were tacitly allowed by jailers, who would also take a cut.

Fast forward nearly 200 years to the 1980s, when scammers in Nigeria began to send reams of paper letters to people across the world. By the 1990s, they used fax machines, and, by the late 1990s, had switched to email.

In the most recent case, a man known only as “Mike,” was arrested, according to the BBC. Over the years, Mike oversaw dozens of people who sent an untold number of emails out across the world, from the U.S. to India to Romania, using the digital age to realize the full potential of the swindle.

Which means that, in 2116, when you receive a holographic message of doubtful provenance promising hidden riches in exchange for a few thousand dollars up front, don’t do it. It’s been tried before.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook