In the 10 days since Russia invaded Ukraine, relations between the first nation to reach space and the Western world have been stripped to the bone.

To wit: Europe's space agency has canceled several launches on Russian rockets, a contract between privately held OneWeb and Roscosmos for six Soyuz launches has been nullified, Europe suspended work on its ExoMars exploration mission that was set to use a Russian rocket and lander, and Russia has vowed to stop selling rocket engines to US launch companies.

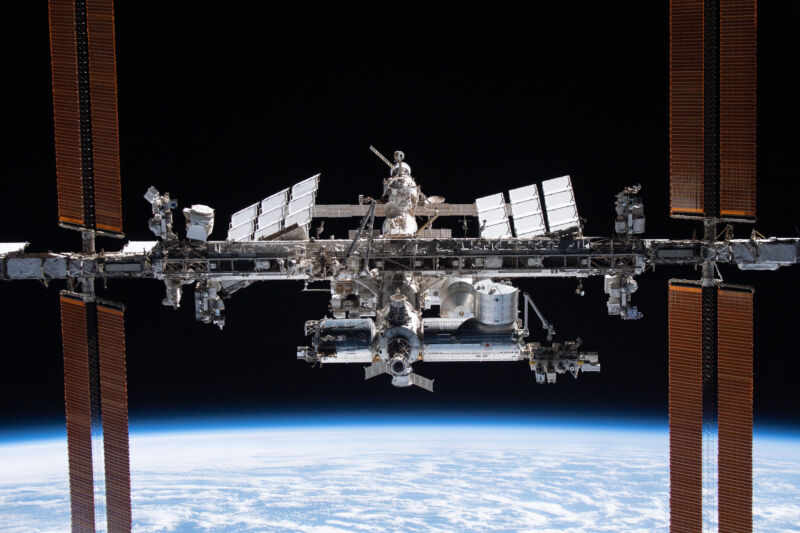

Virtually every diplomatic and economic tie between Russia's space industry and Europe and the United States has been severed but one—the International Space Station.

In addition to these actions, Russia's chief spaceflight official, Dmitry Rogozin, has been bombastic since the war's outbreak, vacillating between jingoistic and nationalistic statements on Twitter and threats about how the ISS partnership could end. Moreover, the Kremlin-aligned publication RIA Novosti even created a creepy video showing Russians leaving their American colleagues behind in space.

But Rogozin has not crossed any red lines with his deeds. Although the intemperate space chief has taken every punitive and symbolic step that Roscosmos can in response to Western sanctions, he has stopped short of huge, partnership-breaking actions. For example, Roscosmos so far has not prohibited NASA astronauts from flying on Soyuz vehicles or recalled Russian astronauts training in the United States, nor has he limited cooperation between Russian and NASA engineers flying the space station from mission control centers in Houston and Moscow.

For its part, NASA has said little beyond expressing a strong desire to continue the partnership. The US space agency's chief of human spaceflight operations, Kathy Lueders, said last week that it would be a "sad day" if NASA and Russia stopped working together on the space station. Flight controllers in the trenches say they continue to operate the station normally.

So the immense space station, constructed over the course of two decades and serving as a beacon of international partnership for even longer, yet flies on. But in conversations with senior officials across the US and European industry, one picture has clearly emerged. The partnership is increasingly tenuous, and no one knows what will happen next.

"The ISS has led a charmed existence," said Jeff Manber, the founder of Nanoracks and a long-time presence in Russia-US cooperation in space. "But it’s never been more at threat. I am not sure what will happen when I wake up tomorrow."

This perilous existence raises serious questions about NASA and Europe's presence in low Earth orbit. If the Russians—or NASA, at the direction of the US State Department—decide to stop cooperating in the coming weeks, what will happen? Can the US side of the space station, which includes modules built in Europe and Japan, be saved? And can the United States accelerate plans to replace the space station given the current tensions?

Losing the station

Regardless of the rhetoric, neither the United States nor Russia wants to lose the International Space Station. Its first component, the Russian-built Zarya module, launched on a Proton rocket in 1998. Now the size of a US football field, the station has a habitable volume equivalent to a six-bedroom house. Its assembly has required more than 40 spaceflight missions, mostly flown by NASA's space shuttle. After two decades, the station remains the bedrock of both the US and Russian human spaceflight programs.

For NASA and the United States, losing the space station would mean the forfeiture of more than $100 billion invested in developing the facility and billions more in provisioning and inhabiting the station. NASA has used the space station for myriad purposes, from a platform to conduct more than 2,500 science experiments to testing human health during extended human spaceflight. The station has also served as an incubator for commercial space. The United States has by far the largest and most robust commercial space industry in the world, led by SpaceX, and most of this activity would not exist today without the station.

NASA officials believe the space station has at least a decade of lifetime left in it, and the space agency has been negotiating with Russia and its other international partners to expand the operating agreement through 2030. While NASA has been taking tentative steps to prepare for life in low Earth orbit after the station retires, such plans remain far from realization.

Arguably more is at stake for the Russian side of the partnership. The reality for Russia and its sprawling Roscosmos corporation is this: without the International Space Station, the country has no real path forward for a civil space program. Russia has not flown a successful interplanetary scientific mission in decades, and now purely scientific work with Western nations is cut off. And while Russia has discussed plans for an ISS-successor, named the Russian Orbital Service Station, it remains just a proposal, with no funding or likelihood of development.

So without the ISS, where could Russia fly its Soyuz crewed spaceship and Progress cargo ship to? One seemingly likely alternative is China's Tiangong space station, the first module of which was launched in 2021. This makes sense given that Russia and China have discussed collaboration in space, including working together on a lunar surface station a decade from now.

However, when China was developing plans for Tiangong, it decided to place the station at an orbital inclination that only takes it as far as 41.5 degrees north and south of the equator. Such an orbit is optimal for launches from Chinese spaceports but is too far south for current Russian vehicles to reach. When Russia approached China about changing Tiangong's orbit to allow Soyuz vehicles launching from Baikonur to reach the station, Chinese officials declined. So in the near term, any Russians going to Tiangong would do so on Chinese rockets.

While China and Russia have a strategic partnership aimed at standing up to the United States and the West, China has been sending mixed messages to Russia about its future participation in space. However, if the Chinese government were to give Russia a firm guarantee on participation in low Earth orbit and beyond, it might give Rogozin an off-ramp from the ISS partnership amid a fracturing relationship with the West.

reader comments

405